It’s review season at work—and somehow performance reviews feel like team-building exercises and trust falls sharing the same calendar invite. Who’s with me🕵🏻♀️?

I love books for two reasons: fiction lets me explore imaginative worlds, and business books provide practical insights. In either case, I’m not the expert. The author leads the way.

Which is why reading Erika Ayers Badan’s Nobody Cares About Your Career comes at a great time. She’s refreshingly direct on many topics, including navigating performance reviews. She writes:

“You can and should do a lot of the heavy lifting [during a performance conversation with your boss]. You can quickly cover your successes, acknowledge your shortcomings, and offer ideas for how best to move yourself, your projects, and your team forward, all of which will disarm your boss and shows that you are willing to learn and improve, and most importantly, contribute. By doing this with a non-defensive attitude and not bringing your ego to the party, you’ve essentially changed the power dynamic from your boss to you.

Be sure sure to use language that makes you sound rational, informed, and articulate. Walk away with an agreement with your manager of what your plan and goals are for the coming months/year. People who go in prepared and with this mindset have stronger reviews and feel better about the discussions.

In advance of your review, spend time anticipating both the good and bad things you’ll hear. Come up with three areas where you are crushing it and three areas where you can improve and grow. Try to anticipate what your boss might say. Be critical and blunt with yourself but not harsh or defeating. The point is that nothing should be a surprise and you should be prepared to offer a plan to improve whatever it is you might hear. (Note to self, you will need to execute this plan).

Saying thank you goes a long way. Most managers dread performance reviews, so show some gratitude and appreciation, and, who knows, they might do the same for you.

Organize your own feedback into logical, meaningful areas. Don’t list twenty places you can improve–distill those twenty things into three main areas of focus. Simplify your critique so that it doesn’t look like an Etch A Sketch of how I suck and the thousand things I could do to fix it.

Your best defense is a good offense. After a short nod to all the great things you have done for work (not for you; remember nobody really cares about you but you–the review is about how you can better help the business), move quickly to your f*ckups and shortfalls. “Here’s what I’ve learned (what I didn’t do so great but will do better); here’s what I’m doing to improve on a lot of that stuff; and here’s what I’m excited about in the future”

Be in charge of your improvement: One week after your review, take initiative, and show your manager your plan. Send consistent and frequent updates on your progress, and, again, ask for feedback along the way. Don’t toss up a bunch of sh*t you’re never going to do, let alone follow up on. When making your plan, make sure it’s something you can sustain. Choose two things instead of twenty, and really commit to implementing them.”

My Quick Notes:

Make a plan. Use your review as motivation to grow and sharpen your skills.

Don’t take candid feedback personally. See it for what it is—guidance on how to make the business (and yourself) better.

As Kim Scott, author of the New York Times bestseller Radical Candor, says: “good feedback isn’t mean—it’s clear.” This can apply anywhere, personally or professionally. When feedback is truthful and constructive, it becomes a powerful tool for improvement.

Think of your review as math. What goals do you want to achieve, and what inputs or actions will get you to the outputs you’re aiming for?

A vision is the difference between doing things randomly and doing things that feel like they matter and add up to something.

-Erika Ayers Badan

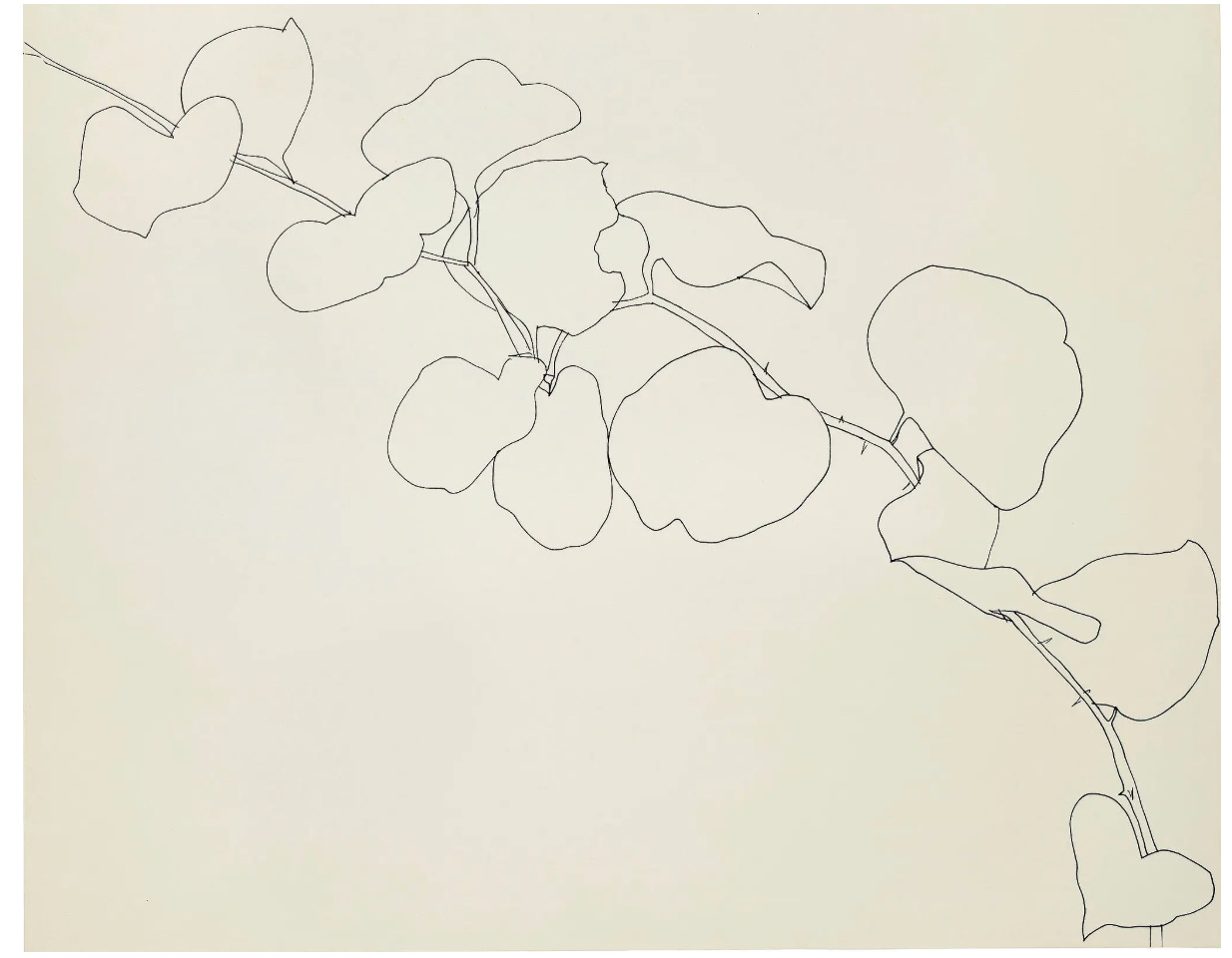

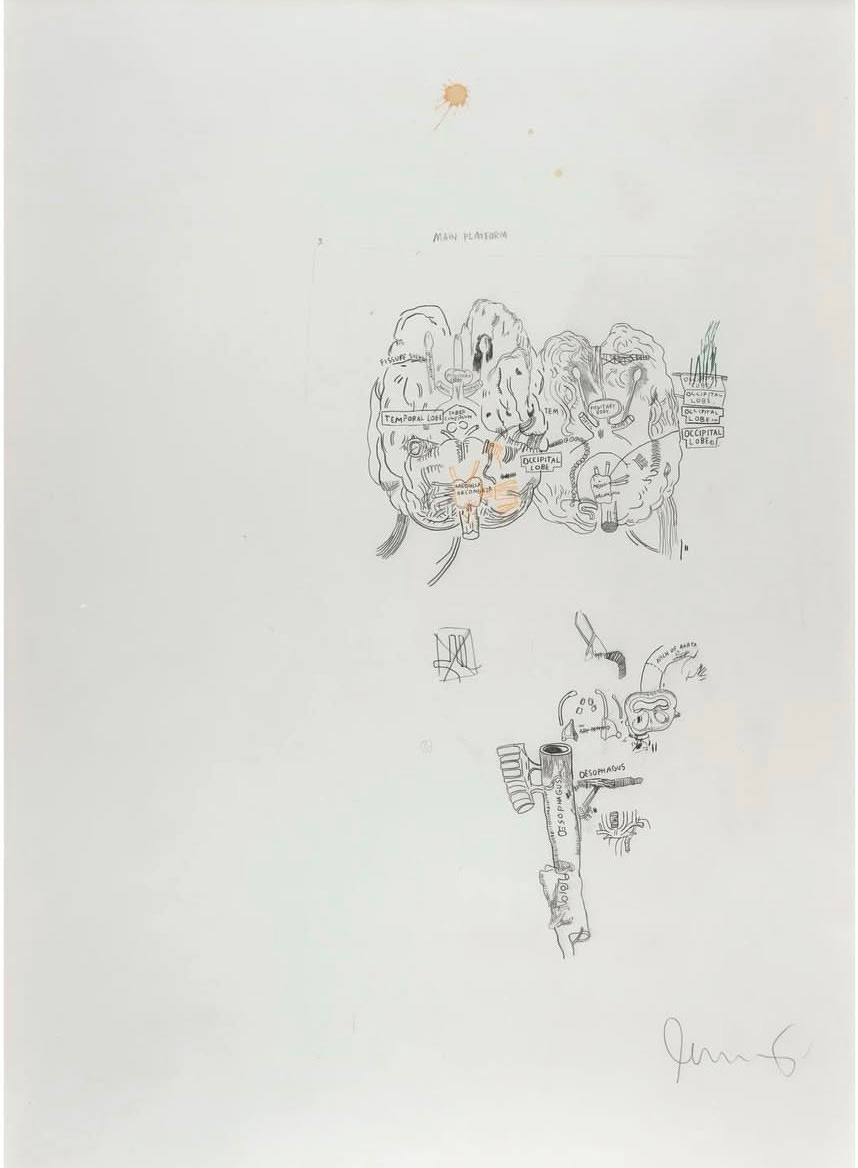

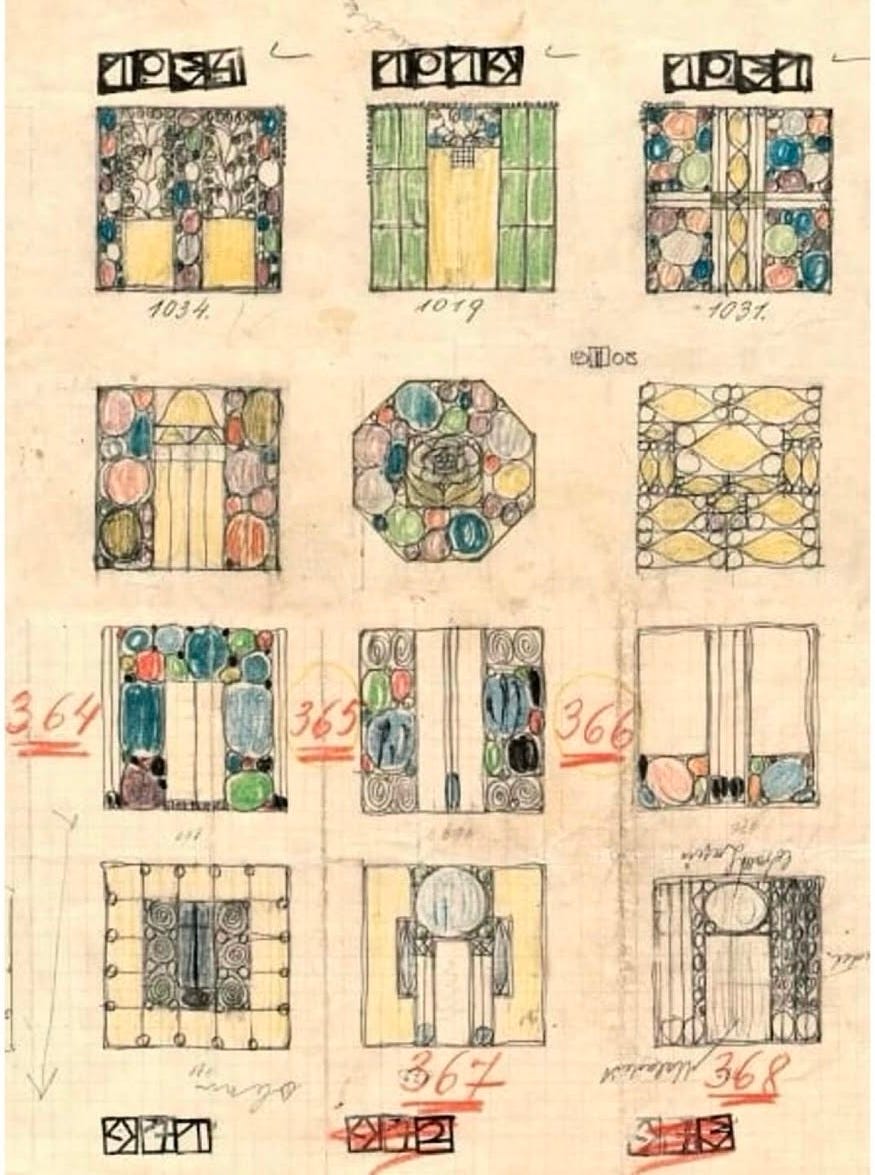

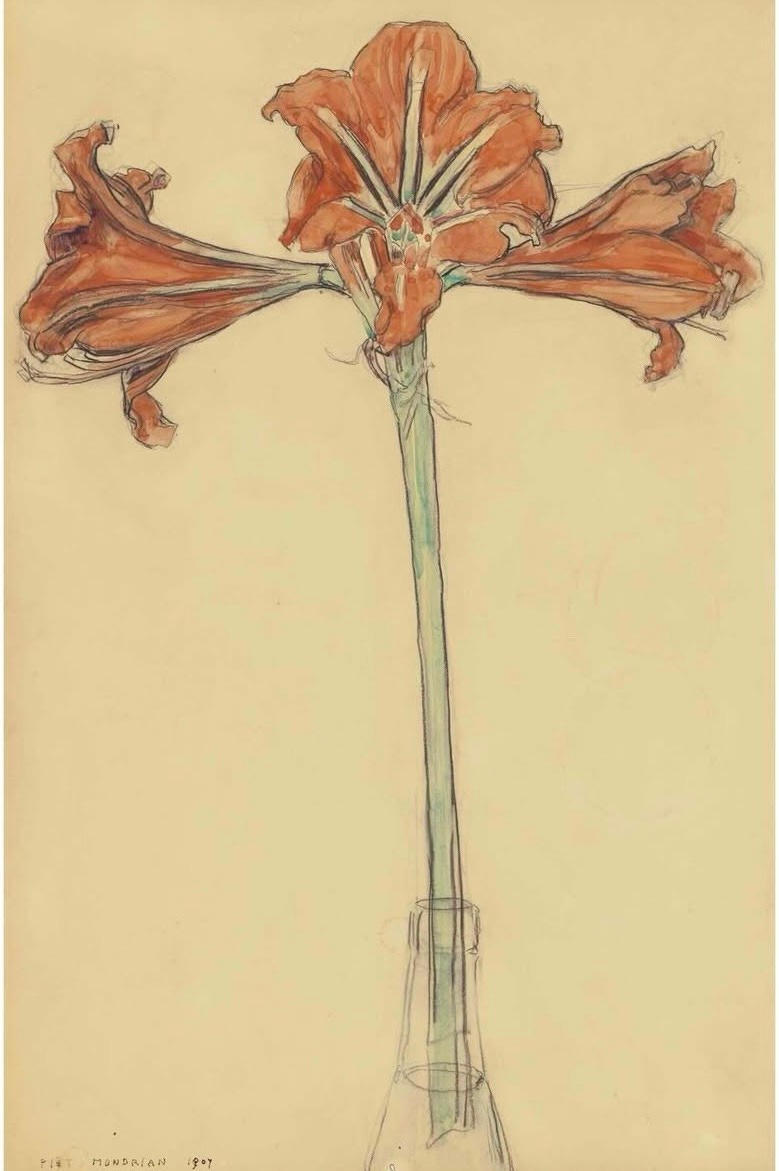

Enjoy the process, even when it feels challenging. Every work of art starts somewhere 🖼️ ✨ Below are a few of my favorites, reposted:

Ellsworth Kelly; ‘Briar’, 1961

Jean-Michel Basquiat; ‘Untitled’, 1986

Josef Hoffmann; ‘Design for Twelve Brooches’, 1926

Piet Mondrian; ‘Amaryllis’, 1907

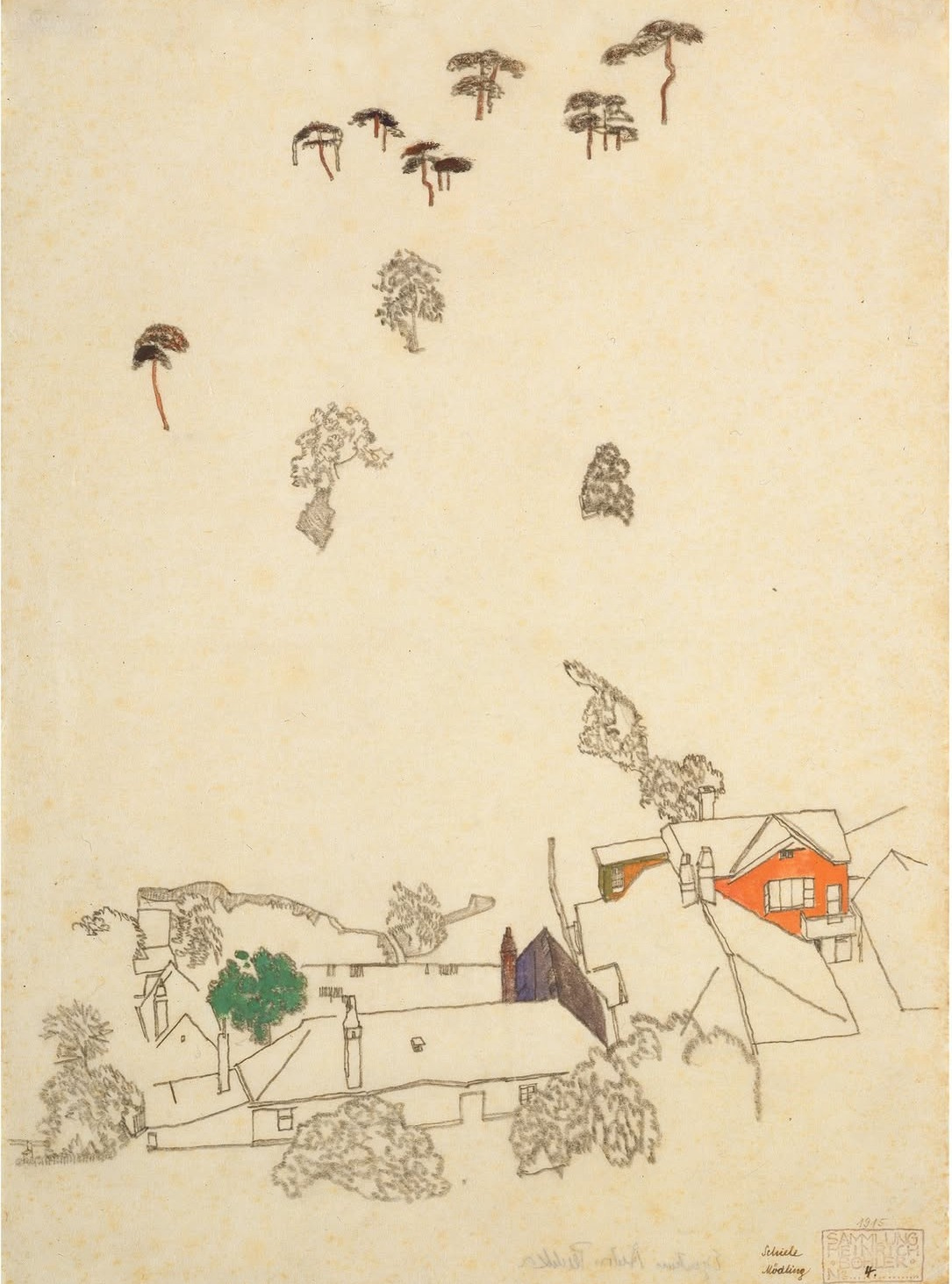

Egon Schiele; ‘Houses and Pines (Mödling)’, 1915